Author, Dr. Yetsa A Tuakli-Wosornu from the Sports Equity Lab has partnered with #WeRideTogether to collaborate and create this athlete-centered IOC Consensus Dissemination Project, which unpacks and elaborates on critical points from the IOC Consensus. The Dissemination Project will provide a 10-part series that highlights key takeaways from the IOC Consensus with visuals, activities, and social content that can be tangibly applied and integrated into sporting communities. This series aligns with the values and mission of both the Sports Equity Lab and #WeRideTogether to promote awareness on the topic of abuse in sports, eliminate inequities in sport, and provide everyone with accessible information on positive values and best practices to keep sports safe and healthy.

When talking with athletes, parents, coaches, and organizational staff across all sports at every level of play, #WeRideTogether is often asked, How do you tell the difference between tough coaching and abusive or toxic coaching?

Some common conceptions include ‘This is just how sports are,’ ‘That’s how I was coached,’ ‘We are getting soft,’ and ‘You have to be hard on athletes to get results.’

There are preferences for coaching styles; however, what is abusive is not a matter of opinion. As discussed in the 2024 IOC Safeguarding Consensus, "...although [interpersonal violence] experiences are highly subjective/personal, research suggests that a felt distinction between healthier and unhealthier relationships can be discerned.”1

When assessing if coaching practices and sporting environments are healthy, safe, and tough versus toxic, abusive, and harmful, we must evaluate patterns and themes of behaviors and dynamics, and the holistic atmosphere. This includes recognizing the short-term and long-term impacts and outcomes of coaching styles and environments on individual athletes, team cultures, and results.

Toxic or abusive coaching falls under the category of psychological or emotional abuse. Whereas healthy, supportive, and positive coaching relies on developing the athlete’s holistic well-being, promoting athlete autonomy, showing care about actively working towards improving team culture, and demonstrating thoughtful and inclusive leadership.2

Psychological or emotional abuse refers to acts and behaviors, most often repeated and persistent, that interfere with and negatively impact an athlete’s positive emotional and social development and self-worth. In athletics, this can happen online and in person and can look like:

- Verbal Acts: name-calling, body-shaming, ridiculing, humiliating, bullying, threatening, discriminating, mocking, spreading rumors, quick oscillation between praise and criticism, promoting disordered eating

- Non-Contact Physical Acts: ignoring, isolating, segregating, denying coaching and guidance, punching/throwing things around the athlete

- Stalking: monitoring, observing, excessively messaging

- Tactics: manipulation, gaslighting, controlling an athlete's social interactions, domination, guilt-tripping, mind games, silent treatment, possessiveness, frightening

Unfortunately, when looking at the research, psychological and emotional abuse tends to be the norm for most athletes. Studies show that “79.2% of athletes reported at least one experience of psychological violence”3 and that psychological violence was the most prevalent form of violence experienced in sports as a child.4 The majority of para-athletes described personal experiences with psychological/emotional abuse.5

Moreover, we must remember that types of abuse, especially in sports, can overlap and intersect. This means that when toxic and abusive coaching practices are in play, there may also be other types of abuse present or heightened risk for other forms of abuse to transpire. These may include verbal abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, hazing, discrimination, and bullying.

Research shows “the role abusive coaching plays in psychological, training, performance and academic outcomes in comparison with coaches who use a more athlete-centered, and humanistic approach.”6 Athletes who experience abusive coaching may have decreased self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and other mental health concerns, as well as may drop out of sport.7 Additionally, athletes may interpret abusive coaching behaviors as normal and may mimic the practices modeled.8

The bottom line: “Athletes rely heavily on their coaches for professional and personal growth. The presence of abusive leadership behaviors can hinder this development, as well as negatively affect an athlete’s performance.”9

Thus, when discerning where the line is for when coaching becomes toxic, we must evaluate tone, intent, feedback style, regulation, topic focus, consistency, motivation, safety, and, most importantly, the athlete's experience.

For example, it is not only about whether the coach is yelling, but rather what they are saying, how they are saying it, and why they are saying it. Is the intent to build the athlete’s skills and resilience or to belittle and demean them? Is the yelling due to an emotional outburst or with moderated intensity and appropriate volume given the environment? Is the content sport and skill specific, or degrading in a personal nature, or off-topic? Is there psychological safety felt by the athlete, team, and the sporting community?10 Does the coach consistently demonstrate emotional intelligence and have strong interpersonal or soft skills?11

Who’s responsible for ensuring that toxic coaching practices are not in place and rewarded?

We all play a role in creating safe and healthy sporting environments. The onus should not be on the athletes, who are not in power. Rather, coaches, parents, organizations, and sporting community supporters can all take accountability for actions and behaviors. This looks like upholding best practices, not turning a blind eye or giving passive permission to condone inappropriate and harmful interactions, and engaging as safe and active bystanders to promote positive culture shifts in our local sporting communities and society at large.

How do we learn where the line is?

First, educate yourself!

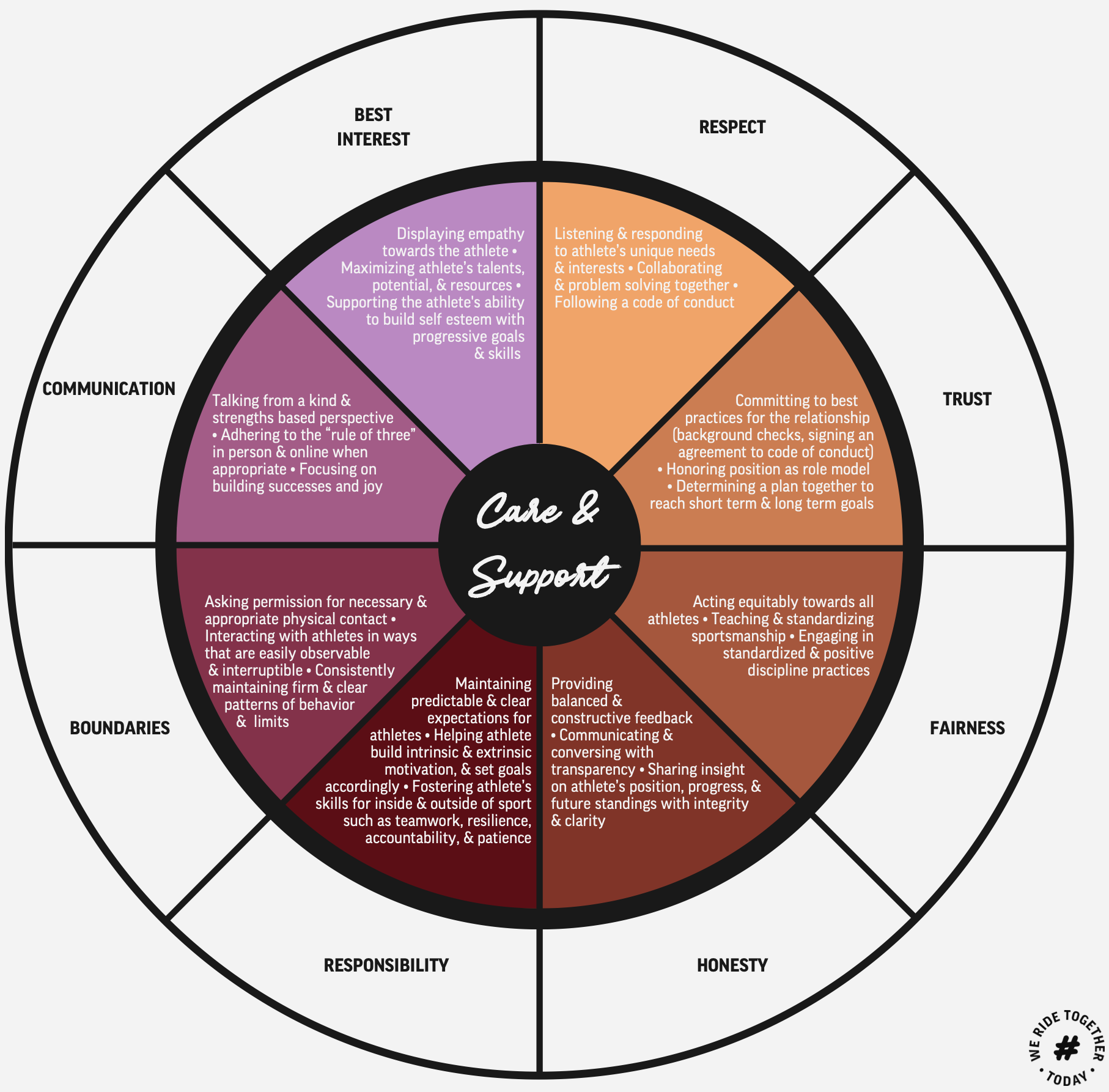

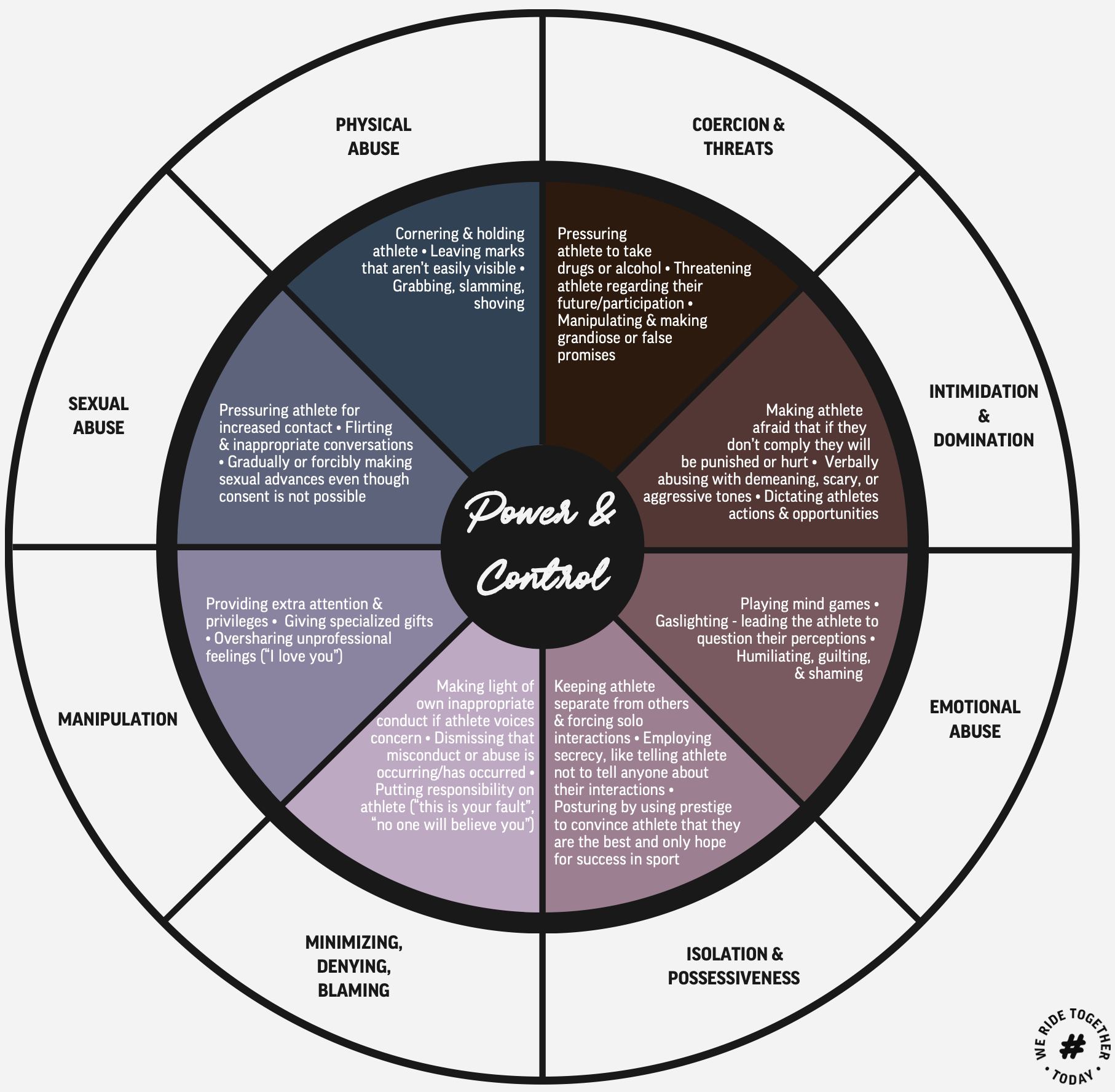

To increase your awareness of tough versus toxic coaching, review the Coach Athlete Relationship Dynamics Diagrams. These side-by-side visuals can be a useful aid in discerning if what you are experiencing and observing is in line with care and support or power and control. “Abusive supervision in sport is inherently derived from the power dynamic that is present between coaches and their athletes.”12

You can also look at the Coach Athlete Relationship Dynamics Diagrams — Icon Version for a visual representation of the differing dynamics and the Coach Athlete Relationship Dynamics Diagrams — Dialogue Version to hear what these dynamics sound like.

Second, engage in some self-reflection and connection:

- Parents:

- Check your bias of projecting the sporting experience you had onto your athlete, or what you may have been conditioned to believe as elements for success.

- Check in with your athletes - Are they having fun? Do they feel comfortable with their team, coach, and in their sporting environment? Do they enjoy practices and competitions?

- How can you promote your athlete to self-advocate and be their supporter and advocate in creating positive change in your local sporting community?

- Coaches and Organizations:

- What is the ‘cost’ of toxic coaching? In terms of emotional, physical, mental, and financial costs for the athlete, team, and organization.

- Is the win worth it? Does toxic coaching really lead to wins? Is the win more valuable than the athlete’s well-being?

- How can I reframe and rephrase my words and actions to be in line with safe and healthy practices and still get the same results?

- Athletes:

- In a dream world, how would you like to be coached in your sport? What makes you feel the best and perform the best?

- What coaching styles have you been exposed to? Do you think what you are/have been experiencing is normal or okay?

- How could your coach improve their coaching and make your sporting environment safer and healthier? How do you think your teammates are feeling?

Third, take this quiz to test your knowledge.

- A female MMA athlete is sparring with a male coach from her gym. They practice together multiple times a week. Every time they spar, he comments how she “fights like a girl” because “she can’t hit as hard as the guys do”. These comments are typically said in jest, but she feels uncomfortable when he makes them.

A. Tough

B. Toxic

The answer is B — toxic. A coach repeatedly telling an athlete they are not as proficient in their sport due to their gender is discriminatory and does not uphold best practices. The athlete also feels uncomfortable when these comments are made, signaling a lack of psychological safety in the sporting environment. The coach could either refrain from making these comments entirely or encourage the athlete to do more strength training and skill-based exercises to improve strength and technique.

- During a cross-country practice, two athletes decide to diverge from the running path and detour to cut a few minutes off their time. When they hit the finish line, their coach is waiting for them. “That was a stupid move,” he says, “No one knew where you were, and you could have gotten seriously injured with no one coming to help you. That is so reckless, and you should know better. You cannot put your safety at risk for a mile time. Never do that again.” This conversation is held away from the other athletes and is spoken at a hushed volume.

A. Tough

B. Toxic

The answer is A — while the language used is inappropriate, the coach has the athletes’ best interests at heart by trying to emphasize the importance of staying with others to promote running safety. The conversation is also held away from other athletes and is not meant to demean or shame them. However, the coach could be more careful with the word choice used to describe the athletes’ behavior. For example, he could have described the move as “careless” or “impulsive”.

- At a rhythmic gymnastics practice, a gymnast accidentally gets their ribbon twisted around their leg during a skill. This throws them off for the next couple of skills in their routine. Their coach immediately begins yelling, “What are you doing?! Get it together! Geeze, can’t you do anything right? Do you even want to be here?” This only makes the athlete stumble more.

A. Tough

B. Toxic

The answer is B — this is toxic coaching. The coach uses belittling language meant to insult the athlete, and the tone of voice is meant to intimidate. If the coach wants to discuss a gymnast’s mistake or their level of motivation, the conversation needs to be held after the routine ends and needs to use appropriate language. The coach could say: “What do you think went wrong with your apparatus? What can we do differently in the future to prevent this from happening?”. This way, the athlete has autonomy in the conversation, and the intention isn’t to shame the athlete.

- A rowing meet is set to occur in a week. One team at a club is a lightweight rowing team, where athletes are supposed to be under a certain weight to be considered eligible for the class. The coach repeatedly tells the athletes up until the meet, “If you want to be here, you need to lose weight and stay under the limit. You are too fat to be eligible for the class. Everyone needs to lose 5-10 lbs before the meet, and you’ll be weighed so I’ll know if you did it.” This is said in a conversational tone to athletes with very little variation.

A. Tough

B. Toxic

The answer is B — toxic. While weight may be relevant for a lightweight rowing team, it is outright harmful to comment on an athlete’s body. If a coach is concerned about issues with weight eligibility, they could instead emphasize the importance of ensuring athletes are fueling their bodies and following nutritional guidelines and could offer opportunities for cross-training.

- After a dress rehearsal for an upcoming performance, the artistic director brings all of the dancers on stage and tells everyone the show is not where it needs to be. The artistic director has multiple issues with dancers missing cues to enter and exit. They state: “Dancers, you all need to pull it together. We know that you’re fully capable of performing well since we’ve been rehearsing for so long. Remember what you’ve been practicing so that you don’t get out there and embarrass yourselves.” The director speaks loudly enough for everyone to hear and with intensity, and does not make any insulting comments toward the dancers.

A. Tough

B. Toxic

The answer is A — this aligns closer to tough coaching. The director speaks intensely but without yelling, and this is a one-time occurrence directly related to a specific rehearsal. The director could further improve their language, however, to be more strengths-based. Instead of saying “So you don’t get out there and embarrass yourselves,” they could say “So you get out there and show all the hard work you have put into your routine.”

Last, share this video to spread awareness and start a conversation with others in your sporting community.

If you or someone you know needs support, please visit our Crisis Resources or Resources for assistance.

Kathryn McClain, MSW, MBA

Program and Partnerships Director at #WeRideTogether

kmcclain@weridetogether.today

References:

- Tuakli-Wosornu YA, Burrows K, Fasting K, et al. IOC consensus statement: interpersonal violence and safeguarding in sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2024;58:1322-1344

- Runquist EB, Adenaiye OO, Sarzaeim M, et al. Associations of abusive supervision among collegiate athletes from equity-deserving groups. British Journal of Sports Medicine. Published Online First: 03 March 2025. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2024-108282

- Parent, S., & Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P. (2020). Magnitude and Risk Factors for Interpersonal Violence Experienced by Canadian Teenagers in the Sport Context. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 45(6), 528-544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520973571

- Pankowiak, A., Woessner, M. N., Parent, S., Vertommen, T., Eime, R., Spaaij, R., Harvey, J., & Parker, A. G. (2022). Psychological, Physical, and Sexual Violence Against Children in Australian Community Sport: Frequency, Perpetrator, and Victim Characteristics. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(3-4), 4338-4365. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221114155

- Rutland EA, Suttiratana SC, da Silva Vieira S, et al. Para athletes’ perceptions of abuse: a qualitative study across three lower resourced countries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2022; 56:561-567.

- Runquist EB, Adenaiye OO, Sarzaeim M, et al. Associations of abusive supervision among collegiate athletes from equity-deserving groups. British Journal of Sports Medicine. Published Online First: 03 March 2025. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2024-108282

- Alexander, K. N., Adams, K. V., & Dorsch, T. E. (2023). Exploring the Impact of Coaches’ Emotional Abuse on Intercollegiate Student-Athletes’ Experiences. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 32(9), 1285–1303. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2023.2166441

- Gupilan, M. (2017). Abusive behaviors in sport: When does a coach cross the line? A synthesis of the research literature (Synthesis Project No. 37). The College at Brockport, State University of New York. https://soar.suny.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.12648/4035/pes_synthesis/37/fulltext%20%281%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Runquist EB, Adenaiye OO, Sarzaeim M, et al. Associations of abusive supervision among collegiate athletes from equity-deserving groups. British Journal of Sports Medicine. Published Online First: 03 March 2025. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2024-108282

- Taylor, J., Ashford, M., & Collins, D. (2022). Tough Love-Impactful, Caring Coaching in Psychologically Unsafe Environments. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 10(6), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10060083

- Ibid.

- Runquist EB, Adenaiye OO, Sarzaeim M, et al. Associations of abusive supervision among collegiate athletes from equity-deserving groups. British Journal of Sports Medicine. Published Online First: 03 March 2025. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2024-108282

.png)