Catering safeguarding resources and education to all types of sporting environments includes examining sport-specific nuances and risk factors potentially contributing to abuse and misconduct. Risk factors often overlap and intersect, but these factors may manifest as different patterns of behavior or themes in differing sports and sport categories. Sports can function as isolated communities and develop cultures and inherent codes of ethics that inform acceptable and unacceptable behaviors.

Inappropriate behaviors may be difficult to discern, as there is no comparison available for healthier alternatives. And when athletes enter sports at very early ages, these behaviors may be all they have been exposed to in sport, leading athletes to believe that potentially harmful behavior is normal. Additionally, abuse and misconduct may be minimized by broader organizations – for example, through phrases like “This is how it’s always been taught” or “Everyone has to pay their dues”. Every sport and sporting environment is unique, and it’s critical that we listen to each athlete’s voice. Simultaneously, understanding these patterns and themes helps support safeguarding initiatives and helps meet athletes and sporting communities where they are in terms of safeguarding needs.

Thus, we have created this Risk Factors Project to promote education, awareness, and understanding of these areas of concern and vulnerabilities in specific sports and sport categories. This project has been supported by evidence-based research, boots-on-the-ground conversations with athletes and other stakeholders, current events, and attorneys versed in abuse prevention. When we hold this awareness regarding sport-specific vulnerabilities, we can better apply these aspects to our safeguarding initiatives. Athletes and parents, coaches, staff, and organizations must learn the risks present in their sporting environments so that they can understand whether seemingly acceptable behaviors or practices are potentially harmful. Coaches and organizations can proactively prevent abuse by paying attention to the unique dynamics in their sport when developing policies and procedures.

-min.png)

Sport Categorization Groups

We have classified sports into 6 categories based on shared characteristics in terms of performance evaluation and gameplay. Each sport is unique, and many sports can fit into multiple categories – for example, golf could be considered both a ball and/or a technical sport, since it is played by moving a ball and is scored based on the fewest technical deductions. These categories were developed to exemplify patterns of potentially abusive conduct that exist across multiple sports with similarities.

Endurance Sports

Endurance sports are sports reliant on muscular endurance, or the ability to contract muscles against resistance for long periods. Endurance sport events are typically won by speed or by the athlete who completes the activity the fastest.

Examples of endurance sports include track and field, cycling, swimming, rowing, multisport events (biathlon/triathlon/pentathlon), sailing, climbing, canoe sprint, and bobsled. Given the characteristics of endurance sports, there are correlating risk factors:

In endurance sports, a major point of concern is Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport, or RED-S. RED-S is a symptom of weight-related pressures seen commonly in endurance sports. The pressure to be “lean” is prevalent in sports involving running (such as track & field or multisport events). In other endurance sports, there may be clear weight restrictions (such as lightweight rowing) that place extreme pressure on having a lower weight. Body talk and criticism, normalized as an element of “competitive advantage,” can blur boundaries and contribute to unhealthy power and control dynamics between coach and athlete.

Similarly, exercise addiction and dependency are phenomena common in endurance athletes. Exercise addiction and dependency occur when excessive training becomes a compulsive behavior that the athlete has no control over. As athletes increase their involvement in sport, their drive to succeed and to push themselves further through practice can bleed into obsession and eventual dependency. This may be formally and informally encouraged externally by parents, coaches, society, and teammates. Excessive training is a form of abuse and neglect, and if we normalize excessive training in sporting communities, we are excusing harmful behavior. Additionally, the duress caused by overtraining and injury can leave athletes psychologically vulnerable to other forms of abuse, such as grooming.

In many endurance sports, female athletes are frequently underrepresented. Female participation in endurance sports is often less frequent than male participation - for example, male cyclists hold 83% of USA Cycling memberships. Female athletes who do participate are often not given the same facilities or resources as male athletes. Female rowers have frequently discussed unequal courses and a lack of necessary facilities — such as showers — at competitive venues. This extends past sport participation and is reinforced by a lack of adequate training, recovery, and nutritional protocols. These protocols are inadequate due to a broader lack of research on female athletes. In endurance sports, where muscle maintenance is critical, having a limited understanding of female-specific physiological needs impairs female participation and retention in endurance sports. Not providing gender-informed nutritional protocols and other relevant medical education to athletes is a form of medical neglect and discrimination.

Endurance sports have a variety of environmental factors contributing to abuse risk. Endurance athletes train in a variety of environments – not just per sport (for example, running on a track versus rowing on the water), but in the broader context of sport (such as cross-training in a gym). Practicing and training in high volumes requires a high level of involvement in sport, and therefore a high level of time spent with coaches and other sporting authority figures. Environmental safeguarding is critical to protecting athletes in these high-risk environments – for example, instituting procedures for water and lightning safety. Not adequately protecting athletes from physical dangers and undue harm is a form of neglect.

Aesthetic Sports

Aesthetic sports are routine-oriented sports that are subjectively scored on elements of technique and artistry. Routines consist of different skills and elements, and each skill is assigned a “difficulty level.” Routines and elements both have baseline scores, from which errors result in deductions and subtracted points. Aesthetic sports are won by receiving the fewest error-related deductions and completing elements with high levels of difficulty.

Sports included in the aesthetic category include artistic and rhythmic gymnastics, figure skating, artistic swimming, diving, cheerleading, and all forms of dance.

The subjective scoring of elements by deducting errors off a baseline score means that, in aesthetic sports, perfection is a goal deemed achievable. This intense scrutiny on avoiding errors to maximize an athlete’s score and competitive success can lead to constant criticism (both internally from the athlete and externally from those around them) and negative impacts on self-esteem. Perpetrators of sexual abuse often seek out emotionally vulnerable athletes with low self-esteem, leaving aesthetic sport athletes potentially more susceptible to abuse tactics.

Aesthetic sports frequently have elements of “partnering” or “stunts”, where athletes are in close physical contact with each other to perform lifts and duet elements. This physical contact is often with sensitive areas of the body, and while this contact may be necessary to complete the element, athletes may not be educated on whether that contact is appropriate/inappropriate in certain settings and on topics like consent. This extends past peer-on-peer interactions when considering coaching stunts and partnering, and the necessity of a coach to “spot” the learning of new and potentially dangerous skills. Athletes who are being lifted or spotted have to hold a high level of trust in the individual catching them, and this level of psychological dependence on a coach or other authority figure can lend itself to grooming and abusive behaviors.

The coach-athlete power imbalance in aesthetic sports is exacerbated by widespread early specialization in aesthetic sports. Aesthetic sport athletes, on average, specialize in their sport – or choose to only participate in one sport – at ages 3-6, whereas other sport categories consider early specialization to be ages 8-10. When athletes begin their sporting careers that young, they build close relationships with coaches that develop over a long period of time. This dynamic lends itself to blurred boundaries between coach and athlete.

Weight is also a critical component of aesthetic sports. The pressure to be as small as possible (and therefore weigh as little as possible) is common across aesthetic sports, whether it manifests as a “competitive advantage” to be a smaller flyer or as a metric on a dance competition score sheet. As mentioned when discussing endurance sports, weight-related criticism being normalized as “part of the sport” can blur boundaries on what constitutes appropriate discussions on athletes’ bodies, and what level of control coaches should have over an athlete’s eating habits. Perpetrators of sexual abuse are frequently adults and peers who can physically dominate or overpower athletes, and being small may make athletes a target for abuse.

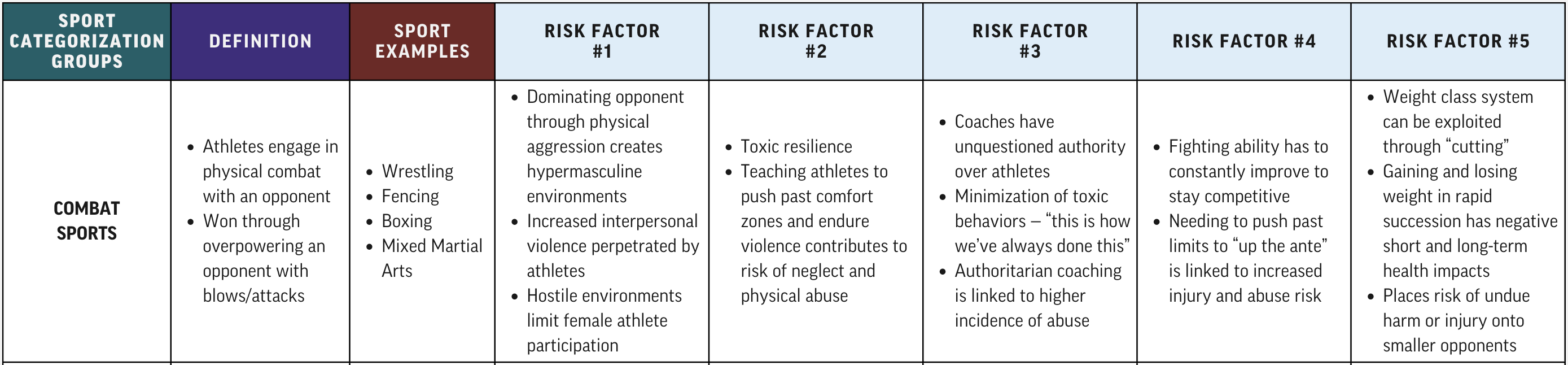

Combat Sports

Combat sports are contact sports where athletes engage in physical combat with an opponent. Combat sports are won through overpowering an opponent with blows and/or attacks.

Examples of combat sports include wrestling, fencing, boxing, karate, judo, and other sports under the martial arts umbrella.

Combat sports often exist as hypermasculine environments, where dominating an opponent through physical aggression is deemed highly valuable. This negatively impacts both male and female athletes participating in combat sports. Teaching young athletes that they “win” through physical violence, rather than through self-control and healthy communication of consent is harmful, and could be linked to increased interpersonal violence perpetrated by combat sport athletes. In contrast, female combat sport athletes report sporting environments that were often hostile and discouraged from expressing femininity. Female athletes may have higher expectations placed on them than their male counterparts, because of misguided notions that “girls are naturally weaker than boys”. This hostile environment is a major reason why female combat sport attrition rates are high. It could also contribute to misconduct experiences – many female athletes are already perceived as “less than”, and may face higher perceived/real retaliation in response to reporting misconduct.

Another element commonly seen in combat sports is toxic resilience. Toxic resilience refers to the pressure to “push through” stress and adversity in the name of pursuing success. Teaching athletes to push past their comfort zones and endure violence contributes to experiences of neglect and physical abuse. This includes overtraining and pressuring athletes to compete while injured.

Coaches in these sports, who are frequently former practitioners of the sport, are often given unquestioned authority over athletes because they have achieved success through enduring pain in training and competition. This can create minimization of toxic behaviors – for example, “This is how we’ve always done it, and you’re the only one who’s uncomfortable with this” – and requires an active effort on behalf of the coach to break the cycle of toxic coaching. This dynamic could be exploited by a perpetrator who has been given passive permission by the organization and society, prioritizing winning over the athlete's well-being. Additionally, authoritarian coaching styles seen in these sporting environments are linked to a higher incidence of abuse.

To stay physically competitive in combat sports, your fighting ability has to improve and adapt. A self-reinforcing need to “up the ante” and increase the difficulty and intensity of elements then presents itself. Sports entertainment – the largest corporations being combat sports organizations UFC and WWE – exacerbate this, as there is an additional incentive to be “entertaining” and increase the danger element for a large audience. This need to push past limits is linked to increased injury risk and subsequent increased abuse risk.

Many combat sports have weight classes to categorize players and ensure that opponents are equally physically matched. This is commonly seen in sports like wrestling, martial arts, and boxing. However, this system can be exploited. Oftentimes, athletes will “cut” weight (or lose up to 10% of body mass) to fit into a lower-weight class. In combat sports, this is done through a variety of methods – for example, restricting food and water, and/or wearing heavy clothing while training to sweat out any remaining “water weight”. This is presented as a competitive advantage – you “cut” before the weigh-in that determines your class, you are poised to fight someone who is in that class due to their actual size, and then you can gain your weight back and easily dominate a smaller opponent. This can be very dangerous. Gaining and losing weight frequently and through extreme measures has negative impacts on your short- and long-term health. It also places the risk of undue harm and injury on fighters who are naturally smaller and are now competing against people well above their weight class.

Ball Sports

Ball sports are sports where players move balls around a field or court. Scoring is dictated by the amount of ball movements – for example, the ball may be placed in a net or over a predetermined goal line to gain a certain number of points.

Examples of ball sports include badminton, basketball, baseball, football, cricket, soccer, volleyball, water polo, handball, tennis and table tennis, rugby, field hockey, and hockey.

Ball sports, similarly to combat sports, can often give way to violent environments. The sports themselves may not necessarily be violent in and of themselves, but violence can be encouraged by broader cultural elements. In sports like hockey, fighting among players is approved as a symptom of overly aggressive play and has historically been allowed due to a lack of regulations. We have seen on-field fighting in numerous other sports, such as football, basketball, and rugby.

Creating a sporting environment where physical violence is not condemned affects athletes and those around them as well. We have seen numerous cases of referee verbal and physical abuse, which can be instigated by spectators, parents, and even the players themselves. Athletes frequently face harassment and abuse from spectators, especially with the rise of gambling in ball sports. We see these effects even among those who are not directly affiliated with the sport – the incidence of domestic and family violence after major team losses increases substantially worldwide. All of these forms of physical and verbal violence can create a hostile and dangerous sport environment, where athletes may not feel safe in their sport.

Ball sports are frequently played in team environments. Even for ball sports competed individually or with two players (such as tennis and table tennis), players often belong to a larger team. Team environments can be havens for peer-on-peer abuse; for example, hazing and bullying. Hazing and bullying have negative impacts on athletic and emotional development, and well-being and often intersect with other types of abuse (such as physical, sexual, and emotional). Hazing or bullying may be seen as natural byproducts of team sports environments and, therefore, ignored or trivialized as part of “paying your dues” or “part of the sport”. However, it is neglectful of adults to ignore incidents of hazing and bullying.

Similar to hazing and bullying is the prevalence of group sexual violence in ball sports and team environments. Particularly in sports like hockey and football, physical aggression and the ability to ‘take down’ an opponent through brute force are key to success. This, combined with the close bonds formed between teammates and socially acceptable misogyny, can create environments where athletes disregard consent because they feel entitled to women and know they can overpower them. This is reinforced by broader sporting organizations, where athletes are frequently simply traded to other teams instead of facing criminal or institutional consequences for their actions.

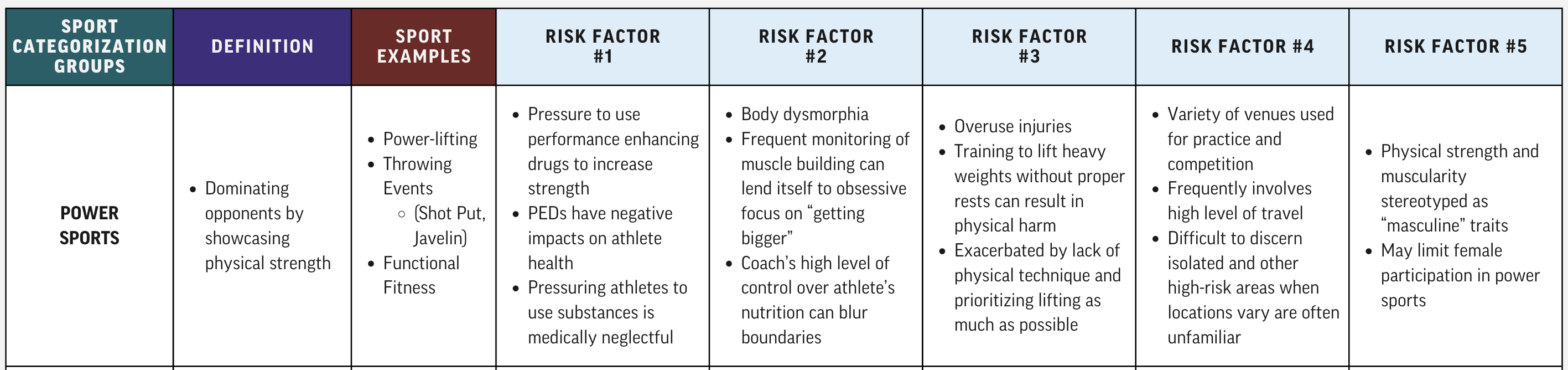

Power Sports

Power sports are sports where the goal is to dominate opponents by showcasing physical strength.

Sports under the power sports umbrella include powerlifting and weightlifting, functional fitness, and throwing events (such as shot put, javelin, discus, and hammer).

Because power sports are so reliant on physical strength, there’s often immense pressure on athletes to use performance-enhancing drugs. These drugs have immensely negative impacts on athletes' physical and mental health, and ‘roid rage’ (or increased aggression as a result of excessive/long-term steroid abuse) has been linked to physical and domestic violence in and out of sport. Pressuring athletes to use and abuse substances with high known levels of risk is medically neglectful and a form of abuse. This pressure may coincide with verbal abuse and body shaming.

Body dysmorphia is frequently seen in power athletics. Body dysmorphia is a condition characterized by obsessive focus on perceived physical flaws. In a sport where the goal is to gain as much muscle as possible, it is necessary to pay attention to physical health and improvement to track muscle gain over time. However, this can also lend itself to not ever feeling like you are “big enough” or that you do not look “big enough”. This may also be encouraged by the broader sporting environment – excessive pressure to gain muscle, accompanied by a coach’s high level of control over an athlete’s nutrition and competition schedule, can contribute to developing body dysmorphia. Body dysmorphia and eating disorders may also fly under the radar in power sports, as these sports are predominantly competed by men, and men historically under-report eating disorders. Body dysmorphia causes severe emotional distress to athletes and is tied to other negative mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. We must coach from a place of care by discouraging athletes from overly fixating on perceived flaws and instead promoting positive body image.

Power sports are often competed through completing many specific events — for example, in power and weightlifting, you are typically competing in squat, deadlift, and bench press. This is also the case in throwing events in track & field. While this provides standardization to objectively assess who is physically strongest, it can also lead to overuse injury. If you are training the same events (and therefore muscle groups) repetitively without taking proper rest, this can lead to overuse of muscles and overall physical harm. Additionally, because these events are standardized to assess physical performance, coaches may teach athletes to “cheat” by lifting without proper technique and instead encourage athletes to just lift as much as they can. Training athletes in this way is medically neglectful and abusive, as it places athletes at an undue risk of harm and future injury. Coaches who work with athletes competing in power sports need to develop expertise across events to ensure athlete safety and to stay up-to-date with the sport’s best practices. Sports can only be sustainable if we are encouraging athletes to gradually develop muscle and follow techniques to prevent early career ends.

Technical Sports

Technical sports rely on accuracy and precision to complete an activity. Technical sports are won by making the least amount of mistakes.

Examples of technical sports include golf, shooting, equestrian, archery, canoe slalom, and curling.

Given that the goal of technical sports is to make as few mistakes as possible, perfectionism and constant scrutiny (both internally directed and externally pressured) are valued and considered critical to succeeding in the sport. Constantly scrutinizing athletes can veer into emotional abuse, and constant criticism is linked to mental health symptoms, worsened performance, and burnout. Negative self-esteem is a prevalent issue because of this factor.

Coaching styles in technical sports may often be authoritarian in nature, as coaches who have produced successful (and, given the nature of technical sports, involve producing technically proficient/errorless) athletes are valued and often go unquestioned. Coaches, even if they lack proper training or education on working with athletes, are often portrayed as someone who can make you “perfect” and therefore guarantee success. Additionally, these sports often have a component of danger - for example, operating a weapon or riding a 1500 lb animal. The heightened stakes associated with participation often lead to a strong deferral to the coach’s expertise for safety reasons and can lend itself to the coach's unquestioned authority. This high level of power over athletes and a lack of broader oversight because these coaches are considered successful enough to operate independently contribute to blurred boundaries on acceptable conduct and may result in minimization or DARVO if abuse occurs.

Coaching technical sports often fosters close relationships between coaches and athletes. These sports are often competed by singular athletes, and coaches work personally with athletes to improve individual performance (rather than working with a broader team to advance). Athletes typically begin these sports at an early age and work with a limited number of coaches. Athletes are often isolated from peers due to the individual nature of the sport, and as a result, close relationships are built with coaches over time. When these relationships are overly close, boundaries are blurred, and other potentially harmful relationship dynamics may occur. This is reflected by athletes often marrying or forming romantic relationships with their coaches during or after their athletic careers. While these athletes may sometimes be adults, consent cannot be properly given when a power imbalance is at play. It may also be reflective of grooming if an athlete who has been training with a coach from an early age enters a relationship with them after they turn 18 (or the relevant age of consent).

Extreme Sports

Extreme sports are sports with a high risk of injury or death and involve elements of the natural environment. These elements include speed, height, depth, and natural forces.

Examples of extreme sports include snowboarding, scuba diving, skydiving, base jumping, auto racing, skiing, kayaking, luge, and skateboarding.

Increased injury risk inherently leads to increased injury rates. Coaches who work in extreme sports need to have high levels of knowledge regarding injury prevention, treatment, and relevant return-to-play policies, as a lack of understanding of these topics constitutes medical neglect. Additionally, injuries and disability status leave athletes vulnerable to all types of abuse.

The increased injury and death risk seen in extreme sports means that athletes have to place a high level of trust in a coach to ensure their safety as they practice and compete. This trust is literally life or death and can give way to psychological dependence and grooming tactics. Simultaneously, if an athlete is not empowered to speak up when something feels “wrong” or feels discomfort participating, they may be at additional risk of injury or death. 54% of NCAA divers said that they were overly nervous or uncomfortable attempting a new dive when they received a concussion.

Extreme sports are increasing in popularity, both in terms of participation and spectating. Therefore – similar to other forms of sports entertainment – there is a pressure to increase the difficulty of skills, gain a competitive advantage, and be seen as more “extreme”. This is very dangerous when considering the life-or-death risk present in extreme sports. Additionally, concerning is the increase in early sport specialization within extreme sports. Considering elements like ongoing brain development, decreased sense of perspective, and perceived invincibility in adolescence, children participating in these sports that could lead to lifelong impairment may not fully understand the gravity of what they are participating in. Minor athletes may be willing to participate, but they hold limited capacity to fully consent.

Many extreme sports also do not have regulations. Skydiving has no federal regulations on planes or heights you can safely skydive from, and base jumping has little to no regulations, which has resulted in death. Not only does this lack of oversight impact the ethics and overall sustainability of the sport, but it also has major implications for physical and mental safeguarding. If little to no regulations exist to standardize key elements of the sport, and having no oversight over sporting environments has been normalized in broader extreme sports culture, it seems unlikely that these environments will have the capacity or desire to standardize acceptable behavior.

Extreme sports involve elements of the natural environment. Oftentimes, the natural environment involves adverse conditions – for example, barometric pressure when scuba diving, or snowy mountain terrain when skiing or snowboarding. These elements can add to risk and require a high level of physical safeguarding (ex., nets, barriers) that may not be in place. These adverse conditions are also often isolated locations – for example, mountains, planes, underwater, or in small boats, or cars. While they may be critical for the sport, these locations may be hard to safeguard in terms of keeping interactions between sports participants observable and interruptible.

As shown, different sports and sports categories have various risk profiles based on their structure, elements, and environments. We must understand and integrate awareness of these informative nuances when developing safeguarding policies and procedures so we can best support athletes and prevent abuse.

If your organization is looking to develop an initial safeguarding policy – or to bolster existing policy – our Safeguarding Essentials Template (SET) Package can help you develop a safeguarding policy, a reporting form, a code of conduct, and a risk assessment. Sport-specific nuances are key to developing protocols that adequately protect athletes. For example, aesthetic sports may want to consider adding provisions related to partnering and consent in their safeguarding policies, and extreme sports can use risk assessments to mitigate unnecessary risks of both physical harm and abuse.

If you are looking for further information regarding safeguarding your specific sport, our Find Your Sport page can provide you with helpful resources.

Stay tuned for subsequent posts dissecting the patterns and risk factors discussed in this post!

If you or someone you know needs support, please visit our crisis resources or resources for assistance.

Annelise Ware, MHS

Program Manager at #WeRideTogether

aware@weridetogether.today

References

- Boudreault, V., et al., (2021). Extreme weight control behaviors among adolescent athletes: Links with weight-related maltreatment from parents and coaches and sport ethic norms. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 57(3), 421-439. https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902211018672(Original work published 2022)

- Burden, R. J., Biswas, A., & Hackney, A. C. (2024). Female Athlete Sport Science Versus Applied Practice: Bridging the Gap. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 19(12), 1518-1521. Retrieved Jun 10, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2023-0390

- Dave, S. & Fisher, M. (2022). Relative energy deficiency in sport (RED – S). Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 52(8), 101242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2022.101242

- Fleming, D. J. M., & Dorsch, T. E. (2024). “There’s no good, it’s just satisfactory”: perfectionism, performance, and perfectionistic reactivity in NCAA student-athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2024.2410282

- Lindsay, R. et al. The Influence of Gender Dynamics on Women’s Experiences in Martial Arts: A Scoping Review. Int J Sociol Leis 6, 297–325 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41978-023-00140-2

- Meyer, M. J. (2024). ‘Martial arts washing’ as a special case of ‘sportswashing.’ International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 17(2), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2024.2424573

- Pankowiak, A., Woessner, M. N., Parent, S., Vertommen, T., Eime, R., Spaaij, R., Harvey, J., & Parker, A. G. (2023). Psychological, Physical, and Sexual Violence Against Children in Australian Community Sport: Frequency, Perpetrator, and Victim Characteristics. Journal of interpersonal violence, 38(3-4), 4338–4365. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221114155

- Ruslan, H. Varieties of Styles of Coaching Work for Children. University of Prešov, Slovakia, Presov, 16-18. https://dspace.uzhnu.edu.ua/jspui/bitstream/lib/55534/1/%D0%A0%D0%B5%D1%82%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BF%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%B2%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B9%20%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%BB%D1%96%D0%B7.pdf#page=17

- Slater, M. (2025). The player we can’t write about and football’s ‘systemic failure’ to deal with sexual violence. https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/6372172/2025/05/31/the-player-we-cant-write-about-and-footballs-systemic-failure-to-deal-with-sexual-violence/

- Stevens, V. (2023). ‘I Never Got Out of that Locker Room’, an Autoethnography on Sexual Abuse in Organized Sports. YOUNG, 32(4), 423-439. https://doi.org/10.1177/11033088231198607 (Original work published 2024)